History

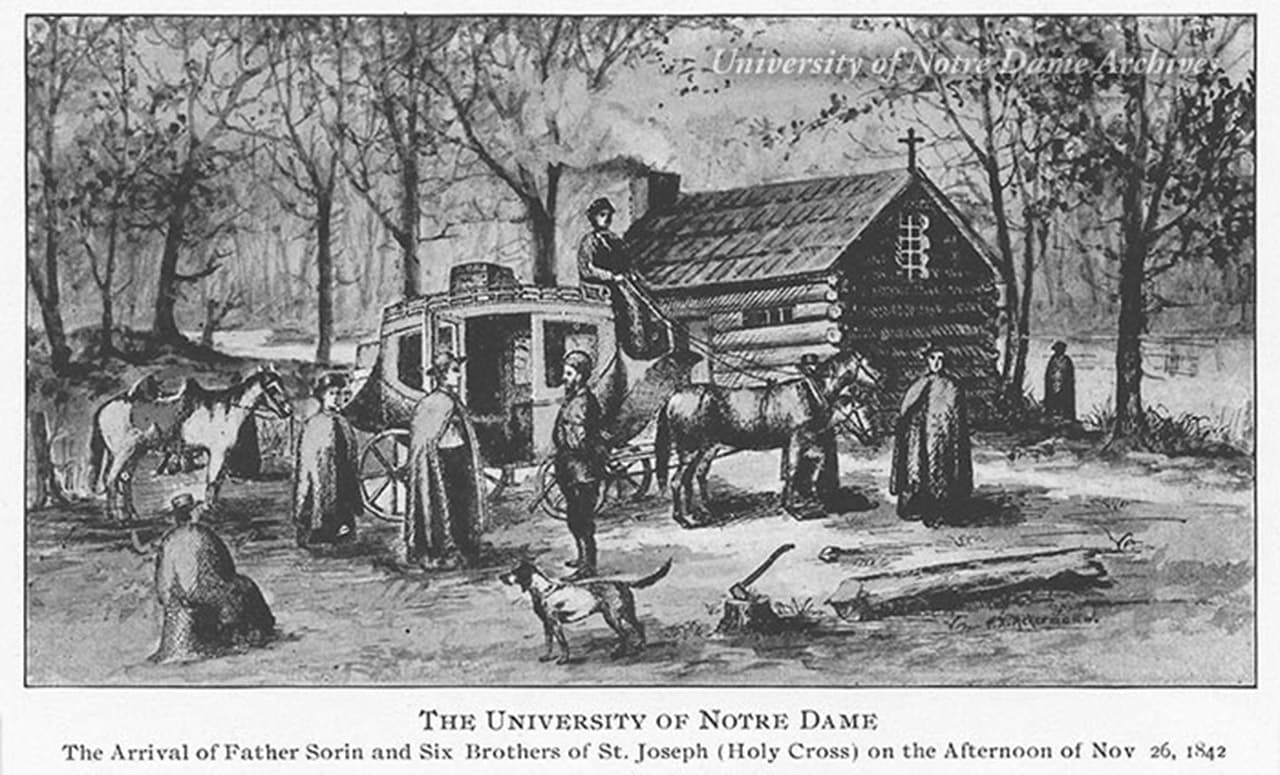

The University of Notre Dame began late on the bitterly cold afternoon of November 26, 1842, when a young French priest, Rev. Edward Sorin, C.S.C., and seven companions, all of them members of the recently established Congregation of Holy Cross, took possession of 524 snow-covered acres that the bishop of Vincennes had given them in the Indiana mission fields.

The founder of the Congregation, Blessed Basil Moreau, had sent Father Sorin from France to America to found a new college in the early 1840s. The Vincennes bishop did not want Father Sorin competing with his own local plans, so he gave the ambitious 28-year-old a two-year timeline to establish a college in northern Indiana where Father Stephen Badin, the first priest ordained in America, was a missionary to the Potawatomi natives.

Arriving with their possessions on an oxcart, Father Sorin thought the two lakes covered in snow were a single lake. A man of lively imagination, he named his fledgling school in honor of Our Lady in his native tongue, “L’Université de Notre Dame du Lac” (The University of Our Lady of the Lake). He had come with $310 and a zealot’s dream of founding a great Catholic university.

The early years were a struggle. One novice wrote that when they were hungry, Brother Vincent “would take a loaf, place it on the trunk of a fallen tree, and with an axe give it three or four heavy blows before he succeeded in cutting a piece.”

Yet Father Sorin wrote Father Moreau in France an optimistic view of his prospects: “Once more, we felt that Providence had been good to us, and we blessed God from the depths of our soul. This college cannot fail to succeed.” He also famously wrote that Notre Dame would become “one of the most powerful means for doing good in this country.”

Nearly 200 years later, Father Sorin’s vision has become a reality—and provided the ongoing mission that Notre Dame continually strives to achieve.

Building a foundation

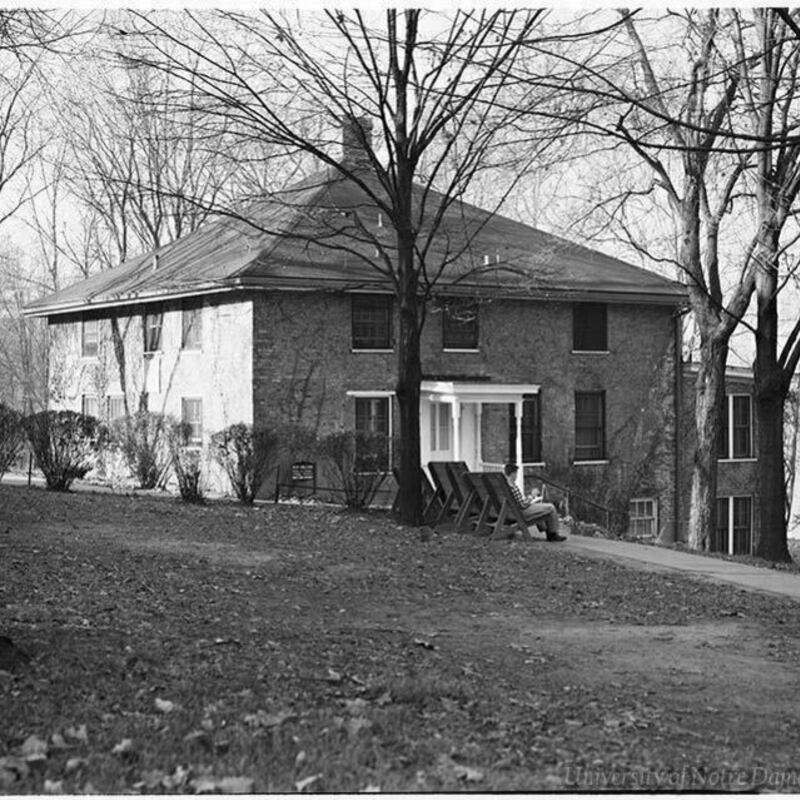

Father Sorin arranged the construction of an administration building even before he had any students or food to feed them. But the founders first built a small, two-story building by St. Mary’s Lake for all activities. Now known as Old College and used by religious students studying to be priests, it is the only original landmark on campus.

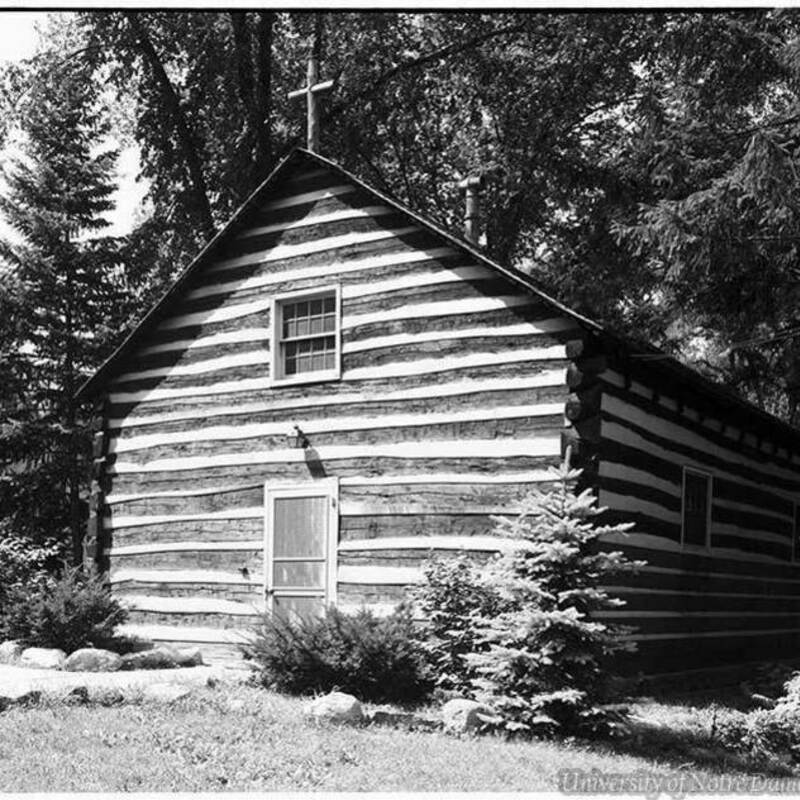

The nearby Log Chapel is a replica of the original, which was built by Father Badin in 1831 as a missionary headquarters but was later destroyed by fire. Father Badin and three other missionary priests are buried in the Log Chapel.

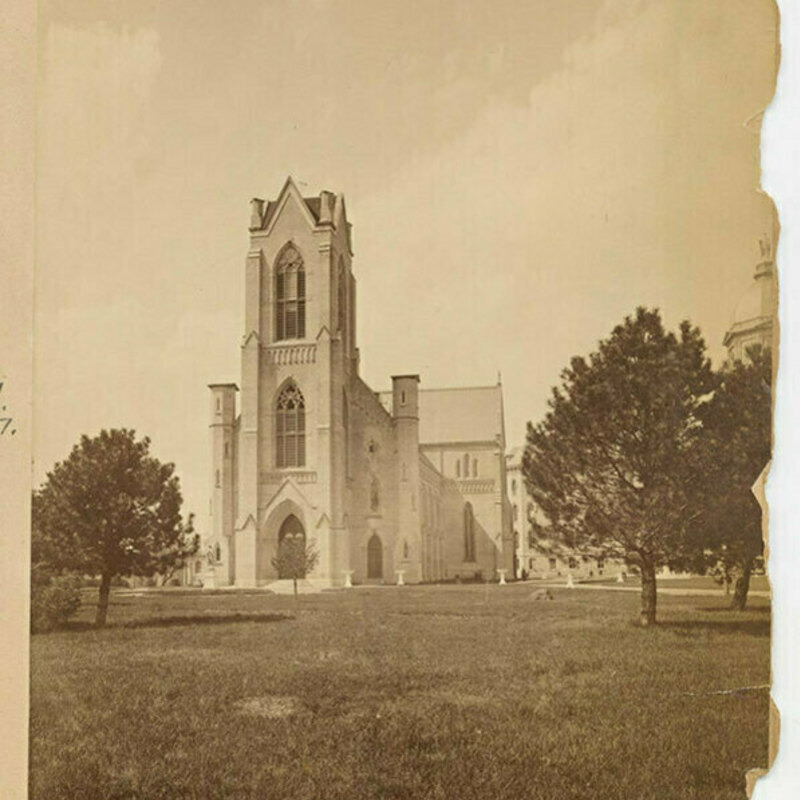

Work began that first summer on a four-story college that opened two years later. Rather than build around the lake, the new building was higher up the hill, at the end of what would become a grand entrance road. On January 15, 1844, the Indiana legislature officially chartered the University.

The Main Building was nearly the whole college then: It contained the dining halls and kitchen, study halls and classrooms, dormitories and offices. The students, priests, and lay teachers lived there. Rev. Arthur Hope, C.S.C., in his history, Notre Dame—One Hundred Years, wrote that Father Sorin had fulfilled the bishop’s condition by launching the college.

“We have seen the almost ridiculous daring of the man, building his four-storied brick college when the student body was almost less numerous than the professors,” Father Hope wrote. “Into that building went his whole heart, for within its walls he hoped to mold a new generation of Christian gentlemen.”

When the Civil War started in 1861, Father Sorin labored to ensure that Holy Cross clerics weren’t conscripted into active fighting. Still, many in the order acted as chaplains for the Union Army, and many Notre Dame students took up arms for the Union, but some for the Confederacy as well.

The iconic Notre Dame moment from the Civil War belongs to Rev. William Corby, C.S.C., who would later become the University president memorialized in a statue in front of Corby Hall. As chaplain to the Union Army’s Irish Brigade from New York, he ministered to a unit famed for its bravery and its casualties. The soldiers arrived at Gettysburg on the second day of the battle following a 13-mile march, depleted in number and spirit. Father Corby gave general absolution to the troops from atop a large rock as they prepared to charge into Confederate artillery fire.

As the student body grew during the Civil War, a new college building was planned. But to save money, the roof of the standing building was removed in 1865 and two more stories and a new mansard roof were added. The next year, a small white dome was added and a white-painted statue of Our Lady placed on top. Brickmaking was one of the first industries of the religious, and the kilns were by then firing 800,000 bricks a year. Tuition at the time was $100.

Fire and rebuilding

The adolescent students known as minims were the first to notice flames curling from the roof on April 23, 1879, and they raised the alarm by yelling, “The college is on fire.”

Students and teachers raced through the building, throwing furniture, books, and belongings out the windows, only to have the broken piles catch fire when the cornices collapsed on them. The fire reportedly ate away the dome supports until the statue crashed down on the building’s interior, spreading the fire and ending all hope of saving the building.

In three hours, the college was gone. Miraculously, no one was killed or badly hurt. But it seemed to some that Notre Dame was finished. Father Corby, then serving his second stint as president, sent the students home but promised that Notre Dame would be rebuilt and open on time the next year.

The story of what happened next has been passed down through the generations of the Notre Dame family. Father Sorin returned from a trip and walked through the ruins, feeling the devastation of the community and signaling to everyone to enter the Church, where he stood on the altar steps and spoke.

“I came here as a young man and dreamed of building a great university in honor of Our Lady,” he said. “But I built it too small, and she had to burn it to the ground to make the point. So, tomorrow, as soon as the bricks cool, we will rebuild it, bigger and better than ever.”

Later that day, the students saw Father Sorin, then 65 years old, stepping through the ruins of his life’s work, pushing a wheelbarrow full of still-smoldering bricks, getting ready to rebuild.

Three hundred laborers worked 16 hours a day, laying 4.3 million bricks, to rebuild the Main Building in time for classes that fall. They rebuilt it from the ground up, and when they got to the top, and came to the place where the dome had been, they built one taller and wider than the one before, and this time—for the first time—they covered it with gold.

Overcoming prejudice

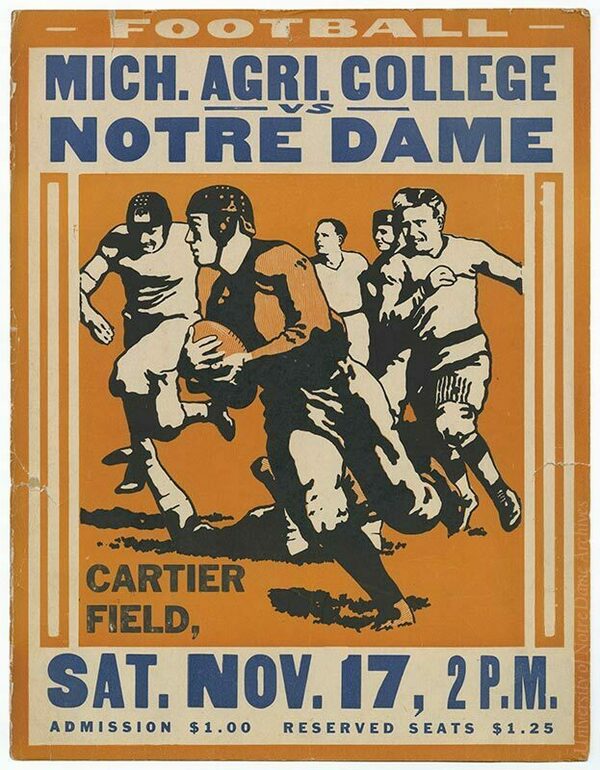

The early 1900s were a time of surging nativist politics that stoked prejudice toward groups that some considered less American, including Catholics. Notre Dame felt the reverberations both near its campus and on the playing fields of its football team, which was growing in popularity under Coach Knute Rockne.

In May 1924, the Ku Klux Klan tried to hold a rally in South Bend, the most Catholic area in a state with a surging Klan. About 500 Notre Dame students showed their objections by storming downtown and ripping the hoods and robes off surprised Klan members, roughing them up in alleys and stealing their regalia.

The riot was finally stopped when Rev. Matthew Walsh, C.S.C., then Notre Dame’s president, ordered the students back to campus. It was Father Walsh who three years later approved the nickname of Fighting Irish for Notre Dame teams because it was preferable to more derisive monikers in use, such as the Papists or Dirty Irish.

Some football teams did not want to play Notre Dame, allegedly due to its Catholicism, which led the University to create a more national schedule. Overcoming this prejudice made Notre Dame a defiant symbol for many recent immigrants who faced discrimination, spawning a network of what are now called subway alumni across the nation.

Wars come to campus

War impacted campus twice in the first half of the 20th century. More than 2,200 Notre Dame students and alumni served in the armed forces during World War I.

Father Walsh and Rev. Charles O’Donnell, C.S.C., continued the tradition of Notre Dame presidents who previously served as war chaplains. Father O’Donnell’s “doughboy” helmet is now a light fixture hanging in the War Memorial entrance to the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, where the motto “God, Country, Notre Dame” is inscribed over the names of fallen Notre Dame men.

Father O’Donnell led the University through the Great Depression, and his successor, Rev. John O’Hara, C.S.C., began a campus building spree with three residence halls in a new North Quad.

During World War II, Notre Dame morphed into a virtual military base. The war was becoming a naval battle in the Pacific, and droves of the young men at Notre Dame left school to join the cause. At the same time, the Naval Academy was ramping up war preparation at a pace rarely seen in human history, and they were in great need of facilities and space to train officers.

Notre Dame reached out to Admiral Chester Nimitz at the Navy, and a V-7 program that trained about 12,000 naval officers was established on campus. Future generations at Notre Dame would credit the Navy for keeping the University afloat during this existential challenge.

National prominence

If Knute Rockne put the small Indiana private school on the national map through athletics, University historians such as Rev. Thomas Blantz, C.S.C., often credit Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, C.S.C., for pushing Notre Dame to become an academic powerhouse as well. Father Hesburgh became president in 1952 at the age of 35 and would lead the University until 1987.

“With his leadership, charisma, and vision, he turned a relatively small Catholic college known for football into one of the nation’s great institutions for higher learning,” said Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C., Notre Dame’s president from 2005 to 2024. “In his historic service to the nation, the Church, and the world, he was a steadfast champion for human rights, the cause of peace, and care for the poor.”

Father Hesburgh, who died in 2015, was one of the nation’s most influential figures in higher education, the Catholic Church, and national and international affairs. During his 35 years as president, Notre Dame doubled its enrollment, added 40 buildings, and grew its endowment from $9 million to $350 million.

Among his many accomplishments were transferring governance at Notre Dame from the Congregation of Holy Cross to a mixed board of lay and religious Trustees and Fellows in 1967, steering the University through the turbulent 1960s, and welcoming women to Notre Dame for the first time in 1972.

Father Hesburgh’s goal of turning Notre Dame into the nation’s preeminent Catholic research University was fully realized when Notre Dame in 2023 was selected as the only Catholic institution to join the Association of American Universities (AAU), a consortium of the nation’s leading public and private research universities.