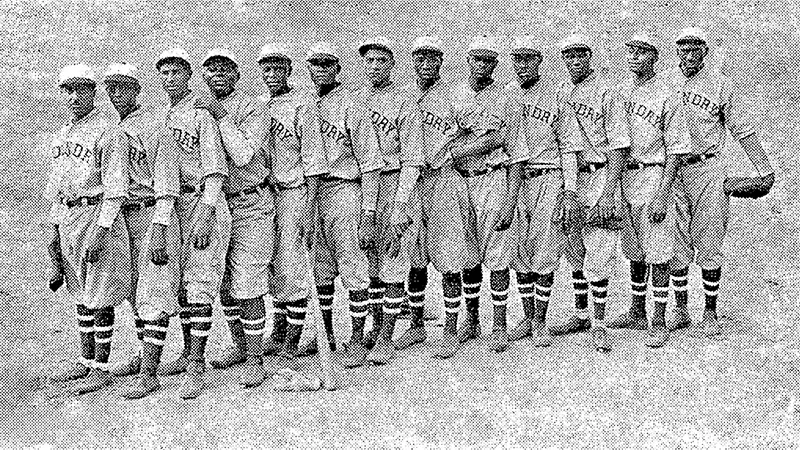

Decades before Jackie Robinson became the first Black man to play in the major leagues, the Foundry Giants—a team of Black players working in the Studebaker factory’s foundry—were making a name for themselves as one of the strongest independent baseball teams in the Midwest.

The South Bend team played in Studebaker’s otherwise all-white industrial league in the 1920s and 1930s and saw about a half dozen of its players go on to play in the Negro Leagues.

Now, nearly a century after John “Big Pitch” Williams faced down his last batter and Dusty Riddle and Alonzo Poindexter cracked their last singles and doubles, the Giants are inspiring a new generation of ballplayers at Foundry Field.

Scheduled to open this summer, Foundry Field is a new public-access baseball field in Southeast Park and a collaborative community project led by the Sappy Moffitt Field Foundation, the University of Notre Dame’s Center for Social Concerns, the Indiana University South Bend Civil Rights Heritage Center, and South Bend Venues Parks and Arts.

Emblazoned on the outfield wall is a mural honoring Poindexter, Riddle, Williams, and their teammates.

Clinton Carlson, an associate professor of design at Notre Dame and one of the coordinators of the project, sees the field as both a living museum and a place for advocacy and change. He hopes it will serve to increase interest in and access to baseball through partnerships with the Boys & Girls Clubs of St. Joseph County and the South Bend Community School Corporation, as well as helping to revitalize the Southeast Neighborhood.

Carlson and colleague Katherine Walden, an assistant teaching professor in American studies, have focused their research and teaching on uncovering and sharing the histories of teams like the Giants.

“Our ultimate goal is to highlight these underrepresented histories in our community that haven’t been commemorated as much as they should have been and to recognize the contributions of people who have not been as visible as they should be,” Carlson said. “But it’s also to activate those histories to create a more equitable and accessible community.”

The Players

Marc Barnes

A 2023 Notre Dame graduate who researched Foundry Giants players Alonzo and Thomas Poindexter in Walden’s Baseball in America class

Clinton Carlson

An associate professor of design whose class helped bring the Foundry Field brand and stories to life

Seabe Gavin Jr.

Athletic director for Riley High School in South Bend and son of Seabe Gavin Sr., who played for the Giants and will be featured in a Foundry Field mural this spring

Thomas “Detour” Evans

Renowned mural artist who painted a mural of the Foundry Giants and players Dusty Riddle, John “Big Pitch” Williams, and Alonzo Poindexter

Michael Hebbeler

A program director at the Center for Social Concerns and co-founder of the Sappy Moffitt League

Matthew Insley

Co-founder of the Sappy Moffitt League and farm manager at Saint Mary’s College

Kiaya Jones

A senior design and Africana studies major who serves as a research assistant on the Foundry Field project

Katherine Walden

An assistant teaching professor in American studies whose class Baseball in America researched the Foundry Giants

‘Opportunities for their voices to be heard’

In baseball, they say that when the best players make contact with the ball, it just sounds different.

For Michael Hebbeler, a program director in the Center for Social Concerns, there was a moment in the planning of Foundry Field when they knew they had something special—when all the pieces came together, and it began to sound different.

It all began when the Sappy Moffitt League started looking for a new home for its adult recreational baseball league. In 2019, league founders Hebbeler and Matthew Insley found a potential fit in Southeast Park.

“Matthew was reading a book about how baseball used to be a sport played in urban settings and how it was built into existing communities,” Hebbeler said. “And he saw this space that looked like it was intended to be a baseball field, although it wasn’t. His vision set this in motion.”

While Insley began focusing on construction of the field, Hebbeler saw the opportunity for arts and storytelling as being completely in line with the CSC’s mission and “Arts of Dignity” programming.

“This is the kind of work we want to be doing,” Hebbeler said. “Our best projects are ones that are deeply collaborative and allow us to build on our relationships with community partners like the Boys & Girls Clubs.”

In partnership with the Civil Rights Heritage Center, they began to brainstorm how the project could also be used to showcase the history of South Bend’s underrepresented teams. A single photo of the Foundry Giants in a book called Baseball in South Bend, by local historian John Kovach, sparked their curiosity.

In 2021, Carlson was brought on board and then reached out to Walden, who researches and teaches about baseball, and Greg Bond, a sports curator and archivist for the Hesburgh Libraries, for help in learning more about the team.

When the group met for the first time, a plan began to take shape.

Walden’s class, Baseball in America, would spend the fall 2022 semester researching the Foundry Giants, while delving into community baseball and Black baseball histories. And in spring 2023, Carlson and his students would bring that research to life through posters and visual materials to be displayed at Foundry Field.

The group also began planning for a series of murals to be painted on the outfield wall (currently the retaining wall for an elevated train track running behind the park) featuring the Giants and other marginalized teams.

Carlson emphasizes how important it was for them to work closely with community partners throughout the process of what he calls “community-activated design.”

“There are advocates in our city who are already fighting for a more inclusive and representational community,” he said. “It’s not about design being the hero that solves the problem. It’s about design assisting the heroes who are already working to solve these problems and maybe have been for decades. It’s asking how design can serve them, empower them, and give them tools and opportunities for their voices to be heard.”

Connecting the past, present, and future

When the spring 2023 semester started, Walden visited Carlson’s visual communication design advanced topics course to share her class’s research. From there, Carlson and his students began exploring how to tell the stories of the Foundry Giants in a way that engaged the community in dialogue about issues of race, equity, and accessibility.

The class began by visiting the Civil Rights Heritage Center and the Notre Dame archives to review baseball materials from the 1920s and ’30s.

“We needed to be very intentional about who we were representing and what we were trying to convey,” said senior Kiaya Jones, a design and Africana studies major. “We took a lot of inspiration from the time the Foundry Giants were playing and chose typefaces and illustration styles we thought would be reflective of the 1920s. Essentially, we wanted to design it as it would have been if they’d had a brand when they were playing.”

While talking with neighbors and community partners to get feedback and approval throughout the semester, the students began creating a variety of materials, including illustrations of the Foundry Giants players used to print baseball cards and life-sized posters.

One of the most memorable moments for Jones was when the class conducted a poster-making workshop with children from the Boys & Girls Clubs of St. Joseph County, who meet just down the street from Foundry Field and who will have access to play on the field once it’s complete.

The students brought 6-foot-tall printouts, along with a variety of paints and stencils, and helped the children create posters of the Foundry Giants players. Their work, signed by the young artists, is now part of a permanent display on the outfield wall. The class also worked with students from nearby Riley High School to create a word-cloud design on the wall.

Meanwhile, Carlson worked with Hebbeler and the Center for Social Concerns to secure renowned muralist Thomas “Detour” Evans as the field’s first artist-in-residence. Evans, a Denver-based artist known for his murals of Jackie Robinson and Martin Luther King Jr., spent a week in May working at the field to complete a mural featuring Williams, Poindexter, and Riddle before the groundbreaking. He also met with Riley students and the Boys & Girls Clubs children during the week to share more about his process.

Evans said that, for him, the project was a chance to connect the past, present, and future, by communicating the history of the team, being present with the community, and hopefully inspiring the next generation in the children he spoke with.

“This was an incredible week,” Evans said at the groundbreaking. “Just coming out here connecting with everyone in South Bend and its past, present, and future was super exciting. I want to thank you for allowing me to be the artist to help tell this story.”

‘Our granddaddy is on the news’

The poster-making session, which was covered by a local news station, ended up being one of many moments of serendipity for the project when a member of the Poindexter family in the South Bend area heard Alonzo’s name in the news story. He called his cousin, Turkesha Poindexter-Mosby, the unofficial family historian, and said, “Our granddaddy is on the news.”

Poindexter-Mosby was excited to discover her grandfather had played baseball and emailed Carlson to learn more. Soon, Carlson and Hebbeler were on a Zoom call with members of the Poindexter family in places as far away as California, Arizona, and Texas, who all wanted to hear more.

“They said, ‘This is amazing. How are you telling the story and what’s next?’” Carlson said. “And we said, ‘You are the story.’ This is exactly how we hoped this project would work, that it’s organic and more people would come to the table and more stories would come to light.”

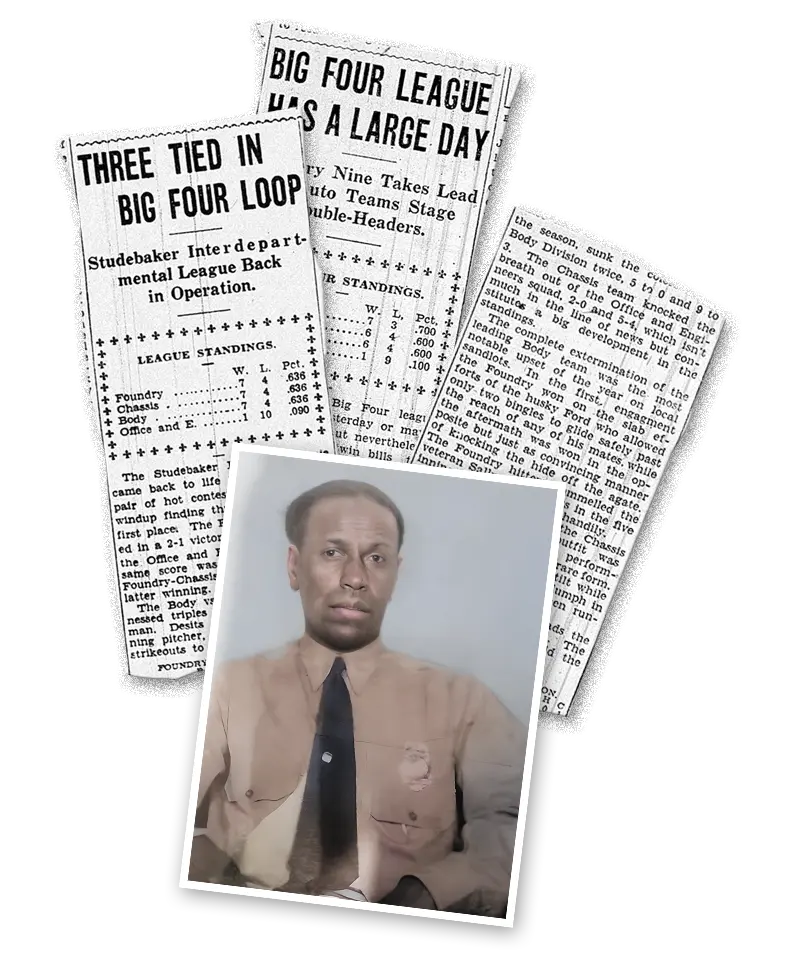

Not only was it special for the family to learn about the research, but Poindexter-Mosby was also able to provide Carlson with a photo of Alonzo in his early days as a deputy sheriff. Carlson age-regressed the photo and shared it with Evans so that Alonzo could be depicted as part of the mural.

And on the day of the groundbreaking, the Poindexter family came en masse to South Bend to see the finished mural and posters. Alonzo’s great-granddaughter Lenisha Lipley spoke to the gathering of more than 100 members of the Southeast Neighborhood and community leaders about Alonzo’s legacy of service and the project’s impact in providing the youth of today “with a lens to South Bend’s rich baseball history and examples of community pillars.”

Telling more expansive stories

Following the groundbreaking, work has progressed rapidly on the field, with the infield and pitcher’s mound completed, irrigation installed, the backstop in place, and the outfield seeded. As the group continues to raise funds, members also plan to build a covered vintage grandstand, covered dugouts, and a scorebooth with a PA system.

The next two murals will also be installed in May. One will showcase a Black women’s softball team coached by Ernest “Uncle Bill” Harris, who played in the 1940s, at the same time as the South Bend Blue Sox of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League.

The other will feature Seabe Gavin Sr., an outfielder-pitcher who played for the Monarch Athletic Club and South Bend Central High School in the early 1930s and for a later iteration of the Foundry Giants, called the Colored Giants, in the late ’30s.

Gavin, too, was held back by racist policies that meant he could not play in “sundown towns” that barred Black Americans from entering the town after sunset. But despite that, he batted an astonishing .649 in 1934 and led his high school team to win the Northern Indiana Eastern Division Championship, by hitting three home runs and driving in seven in the 10–3 victory.

In 1935, Gavin left school to join President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps and, years later, he was humble about his ball-playing days, according to his son Seabe Gavin Jr.

“He would say, ‘Yeah, I played baseball at Central,’ but that was it,” said Gavin Jr., the athletic director for Riley High School. “So, as a kid, I never knew what my dad did—but I knew who he was. He taught us that if you work hard and do everything right, you don’t have to worry about wins and losses, you don’t have to worry about the accolades. They’ll take care of themselves. Because hard work always pays off.”

Carlson, Walden, and Jones—who has stayed on as a research assistant after last spring’s class—are continuing to research additional teams in the area and look forward to highlighting more players who have not received the recognition they deserve. And Hebbeler is offering a one—credit course through the Center for Social Concerns called Arts and Social Change that engages with the stories while exploring themes of human dignity and access.

In addition to their current research into Uncle Bill’s softball team, they are also looking into two local Latino teams from the 1970s that Walden’s students will research in fall 2024 and an Indigenous team that played around the turn of the 20th century.

“I’m so excited to dig in again,” Walden said. “There’s clearly an affinity for baseball in South Bend, with the Blue Sox, the Silver Hawks, and now the Cubs. But we need to understand what got us to this point, what created the passion for baseball we see today, and we need to ensure that the game is accessible to all of the young people in our community. And we do that by investing in our community structures and by telling more expansive stories.”